Promoting awareness of the archaeology and history of North Devon

Copyright © 2015 North Devon Archaeological Society

The Parracombe Survey -

(Newsletter Summer 2001)

THE PARRACOMBE SURVEY: More than any of our plans, the field-

There are 30+ buildings to be surveyed, so assistance is required. We plan to begin the survey this September.

We hope to get a small number of students from Exeter University to assist, but we

also want volunteers from NDAS. This project has the potential to become very important

for the archaeology of North Devon, so clearly we want members to get involved. If

you would like to join in building survey and test-

Terry Green, Chairman.

Parracombe Project: First Report -

(Newsletter Summer 2002)

I. Building Survey and Test-

As promised in the Summer 2001 Newsletter, the Parracombe Project got under way in

September. It began with the limited aim of surveying buildings and testpitting at

Bodley, a settlement focus to the north-

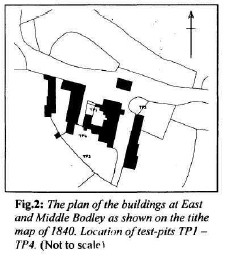

The house at East Bodley turned out to be complicated. The building bears two datestones,

one (1754/5) on a cross-

The first test-

The second test-

The third pit (TP3), dug in the area to the south which, on the 1840 tithe map, is

shown as a stock yard, produced exclusively 20th century material. These pits were

a disappointment after TPl. At a slightly later date, a fourth pit (TP4) was dug

in another part of the former yard and this time produced a large quantity of pottery

fragments with a date range similar to that found in TPl. This was also redeposited

material dumped as make-

The third pit (TP3), dug in the area to the south which, on the 1840 tithe map, is

shown as a stock yard, produced exclusively 20th century material. These pits were

a disappointment after TPl. At a slightly later date, a fourth pit (TP4) was dug

in another part of the former yard and this time produced a large quantity of pottery

fragments with a date range similar to that found in TPl. This was also redeposited

material dumped as make-

All pits were dug down to natural and all produced unstratified post-

Walner Farm. The latter is a complex of buildings lying in an out-

The house has smoke-

II. Field Boundary Survey:

With the FMD crisis (hopefully) out of the way, the field boundary survey was able

to proceed. East Middleton Farm, taken on as a test-

In the Autumn/Winter Newsletter 2001, page 20, Figure 4, a long curving boundary

was singled out as early and significant. Interrogation of the data-

III. Holworthy Farm:

During last year, Dr Ralph Fyffe from Exeter University had been in search of suitable sites on Exmoor for taking core samples of peat for palaeoenvironmental analysis. Among others he found a suitable location below Chapman Barrows on the land of Holworthy Farm.

Anyone who has read through The Field Archaeology of Exmoor (Riley and Wilson-

Holworthy Farm presents the opportunity to carry out every type of survey, and to

make a substantial contribution to the ultimate goal of the Parracombe Project, a

complete parish survey. We hope that many members will want to become involved (phone

Colin: 01271 882152 or fill in the volunteer form on page 19-

The excavation at Higher Holworthy is a highly desirable goal, but at present we still need an experienced excavator to take it on as a commitment.

Terry Green.

Getting back to the NDAS Parracombe Project -

(Newsletter No 11 2005)

The Holworthy excavation came out of the NDAS Parracombe Project which we set up

in 2001. The aim was to conduct an archaeological/historical survey of this interesting

parish as a contribution to the understanding of the evolution of the North Devon

Landscape. The project was to include documentary history, a survey of the buildings

of the parish, a field-

The Holworthy Farm excavation, conducted between 2002 and 2005, has been a signal

achievement, but now that we are wrapping it up, we can get back to plan A. The first

thing to do in the field is to complete the field-

The purpose of such a survey is to provide data with which to begin to peel away

the layers of the historic landscape. Through previous survey work we have begun

to establish that certain physical characteristics of the existing hedge-

Currently a number of NDAS members are offering their voluntary assistance with the

Victoria County History project recently initiated on Exmoor. The purpose of the

project is to combine documentary and field evidence to produce parish histories

of a number of South Exmoor parishes. Parracombe is not included, but what we are

trying to do there parallels the VCH project. With this in mind, Rob Wilson-

• Consider the Bronze Age evidence in the light of Holworthy, looking at other enclosures, Martinhoe Common, South Common, the flint scatters, etc;

• Draw together existing information on field monuments such as Chapman Barrows, Voley Castle, Holwell Castle, etc.;

• Examine the field-

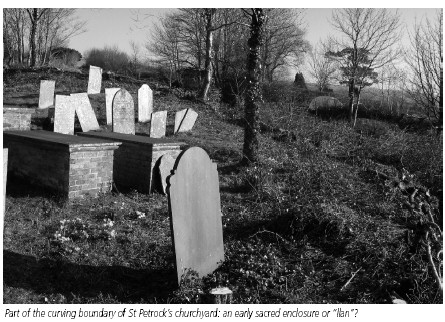

• Consider the origin of the settlements, both the principal nuclei and the farmsteads (Parracombe Churchtown with the church of St Petrock, Bodley, Middleton, Rowley, Holworthy, Holwell, etc.);

• Develop models to trace settlement evolution;

• Within this framework, consider recent influences such as the railway, road patterns, changes in farming, the World Wars, modern communications, etc.

The questions raised should be considered in the light of Dr Martin Gillard’s PhD thesis on the Exmoor landscape, Dr Judith Cannell’s thesis on the archaeology of Exmoor woodland, the Holworthy dig, building records, the work going on under the VCH umbrella.

This all amounts to a thorough investigation of the landscape with opportunities for all the main techniques such as fieldwalking, geophysical survey, earthwork survey, standing building recording, documentary research, oral history. A number of elements here tie in with the parish history being developed by the Parracombe Historical and Archaeological Society.

A very important contribution to the Parracombe Project was recently made by Mary Houldsworth and Jim Knights, when they completed a geophysical survey of Holwell Castle.

And currently Margaret Reed is doing a documentary sweep in the record offices, a necessary and important step towards providing a framework of recorded history for the archaeological evidence.

From evidence gathered in these ways, we can piece together a parish history which

goes beyond the written records. Ultimately and ideally one would like to be able

to trace a continuous development from the first arrival of Mesolithic hunter-

Documenting Parracombe -

(Newsletter No 12 2006)

As part of the NDAS Parracombe Project, I was invited to ‘do a documentary sweep

in local record offices…towards providing a framework of recorded history for Parracombe’.

On re-

Unfinished History, makes my task much easier than starting with a blank canvas. I hope that I can provide some answers to the queries, fill in some of the gaps and maybe add a few extra pieces of the puzzle along the way.

May I at this point make a plea for any documents or records relevant to Parracombe’s past that may be in private hands? I have already been given access to some such papers, and would welcome more if available. So, what information have I located so far in this quest for relevant documents? Domesday is of course the most likely start, failing a Saxon charter or two that have, so far, not materialised.

From the time of the Norman Conquest onwards life in this upland Devon parish can be traced through official records running like a thread through a thousand years, from a time when the parish as such did not exist and much of it was uncultivated heath and moor. The survey of 1086 records three manors or estates, each previously owned by Saxons: Parracombe, Middleton and Rowley. These later grouped together to form the parish as we know it today.

Fourteenth century tax returns based on goods or land indicate how the population gradually increased in numbers and wealth, thus creating the need to bring more land under cultivation. Through Norman, Plantagenet, Tudor and Stuart reigns a number of surveys record names and other details of the inhabitants and the development of the farms. Sheep, which provided the bulk of the population with a living, figured largely in the economy of the parish for centuries.

There has been a church in Parracombe for at least eight hundred years, maybe more. The patrons of the living and the rectors they appointed during that time exerted significant influence upon the lives of the inhabitants, especially in the matter of tithes.

In the sixteenth century the records show how Parracombe prepared for the possible arrival of the Spanish. Each male was named and trained with longbow, musket or pike if fit to do so, or if unfit, but with means, was charged with providing the equipment. In the event, no invasion occurred. Other surveys tell us how many fire hearths there were in 1674, how the land was used and what taxes were raised. Wills provide us with an insight into the wealth of some of the local gentry and which properties they owned.

In the nineteenth century we have the tithe maps and awards and the census returns.

In the twentieth century, perhaps the biggest changes of all in lifestyles occurred.

Communications have evolved over the years, from track-

Field Boundary Survey at West Middleton, Parracombe -

As part of the Parracombe Project, NDAS members have during the last eighteen months

or so -

Boundaries represent the definition, protection and control of land. The process

of enclosure continued over many centuries culminating in the Parliamentary Inclosures

of the 18th and 19th centuries. Boundaries of this period are usually recognised

by their straight lines and right-

The above is a simplification -

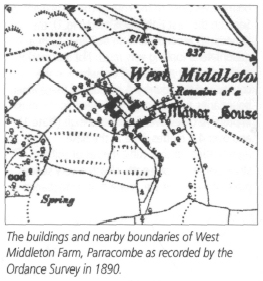

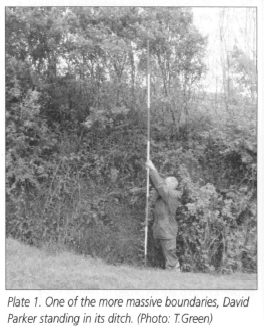

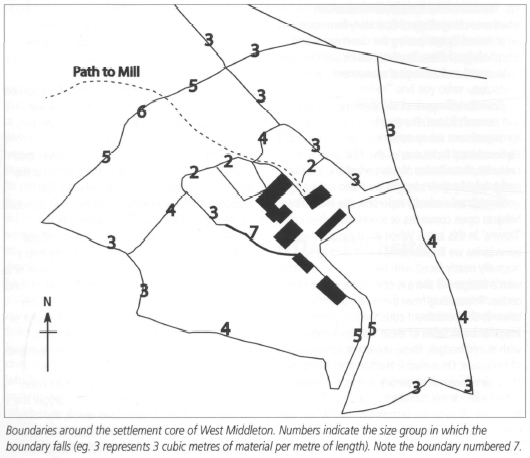

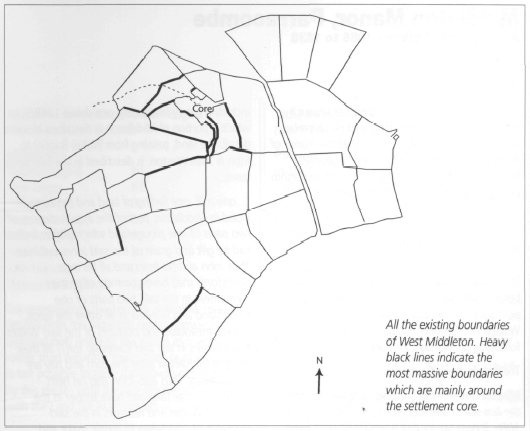

At West Middleton, which in the medieval period, was the core of the manor of Middleton,

we have found a number of very massive boundaries close to the core of the settlement.

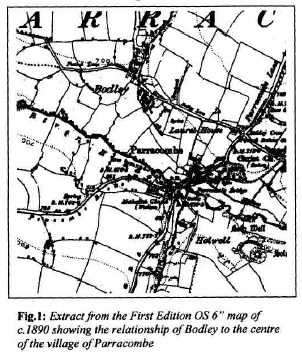

Seen on the First Edition OS map (Fig.1), the boundaries around the farm buildings

form a quadrilateral looking very much like a manorial enclosure such as is found

elsewhere in the county and the country. A number of these inner boundaries are very

massive indeed, in the most impressive cases over 2.5 metres high (Plate 1) and over

4.0 metres wide at the base representing up to 7 cubic metres of soil and stone per

metre of length: clearly a very serious piece of work. We are aware that hedgebanks

become eroded and are periodically maintained, so that over time their dimensions

can change. Since the effort required to move soil (in an unmechanised age) would

always be the same, and as labour becomes more expensive and motives change over

time, it seems fair to assume that a rebuilt boundary will be less rather than more

massive than the original. Therefore when we come across a length of very massive

boundary, we assume it represents something like the original. BoundaryWM111A (shown

in Fig.2 with a heavy line and the number 7) represents this well. This south-

Middleton Manor, Parracombe A Preliminary Survey -

Margaret Read has been applying her research skills to the documentary record of Parracombe. She was asked to look particularly at the manor of Middleton* and has demonstrated how the extent of the manor and the pattern of ownership and occupation have developed over nine centuries.

(* Divided probably since the 15th century into West and East Middleton.)

The Saxon manor of Middleton, owned by Edmer before 1066, became one of the many estates across a dozen English counties awarded by William I to Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances following the Norman invasion.

The Domesday entry reads:

Middleton -

This description of the manor in the Domesday Survey of 1086 is, to say the least,

confusing. While the ancient boundaries remained into recent times, the extent of

cleared, and therefore taxable, land in the eleventh century is uncertain as land

measurement took account of soil quality. Also the terms hide, virgate and furlong

were not constant and bore little relation to modern acres or hectares. However,

it has been assessed that Middleton was taxed on 359 acres in 1086. During the next

two centuries several changes of overlordship are recorded in Feet of Fines, including

a very interesting one dated 1248/9, in which a portion of Middleton is described

in some detail. The land, passing from Walter Baghal to John & Joan Weston, is described

in the following terms: -

'... one mill, one ferling of land and ten acres of wood in Middleton, part of the

appurtenances of two parts of one ploughland which Walter before had by gift and

grant of the said John and Joan. Thus John and his heirs and all his men henceforth

shall have common of pasture everywhere in the said two parts of one ploughland and

likewise in all other the lands, woods, meadows and pastures of the said Walter and

his heirs in the said township tor[7] all their cattle in Middleton after the corn

and hay are carried away. Thus also John and his heirs henceforth may take and have

timber in the woods of Walter and his heirs in the said township of Middleton to

repair, make and sustain the mill by view of the foresters of the said Walter and

his heirs for ever...' (Feet of Fines, Devon and Cornwall Record Society 1912,Vol.1,

No. 461, 29.10.1248-

Here is evidence that a mill had been introduced since 1086 and that the woodland

had increased in size, the three acres having now grown to at least ten, bearing

in mind that this is only a portion of the entire Middleton estate. By 1332 the Lay

Subsidy Roll recorded eight people in Middleton liable to pay the tax, which was

assessed on at least ten shillings' worth of moveable goods in rural areas, with

the tax being levied at one fifteenth. Here is evidence that Middleton was occupied

by several families of sufficient means to be taxpayers rather than labourers. The

first name on the list is probably that of the descendant of Walter Baghal mentioned

above in 1248: -

Middleton

Baldwin Baghel 8d

John Greye 8d

Henry de Hele 10d

Thomas de Hele 18d

John Puddyng 8d

Adam Bryan 8d

John Horsmer 10d

Thomas de Brydewyk 12d

Tax assessments, muster rolls and other official returns from the sixteenth century onwards unfortunately relate to the parish as a whole rather than separate 'townships' or manors, so it is not possible to trace he growth of Middleton by this means until the late eighteenth century, with the Land Tax Assessments of 1780 to 1832:

Land Tax Returns 1780: Middleton Manor (North Devon Record Office)

Property Proprietor Occupant

Voley Henry Beavis, Esq. George Pugsley

Heal Henry Beavis, Esq. Nicholas Ridd

Walner & Gratton John Crang John Crang

Heal &Winslade Meadow John Crang J John Crang

West Middleton Henry Down, Esq. Richard Dovell

Heal Richard Dowell William Frost

Middleton John Slader, snr. John Slader

East Middleton Henry Beavis, Esq. Henry Harding

Grattons John Prowel Humphrey Merchant

Heal Mr. Berry Thomas Challacombe

East Middleton Henry Harding Henry Harding

Heal Richard Tucker Charles Blackmore

Invention Timothy Harding Timothy Harding

Tithe Award 1838: (North Devon Record Office)

Following on from the tax returns, the Tithe Award of 1838, complete with detailed

map of the whole parish, is a complete record of land use and property ownership

at that time. There were fifteen separate land-

The figures in 1838 are a far cry from those of Domesday. Seven hundred and fifty years after the survey the rural manor of Middleton had become a thriving community within the parish of Parracombe, with every occupier engaged in some form of agriculture, while the landowners, as before, were not all resident. Robert Newton Incledon was Recorder for Barnstaple and lived in Pilton, while Amelia Warren Griffiths also had strong connections in Pilton and owned property in several parishes in Devon and elsewhere.

This preliminary survey necessarily ends with the Tithe Award of 1838. Middleton retains a landscape of farmland and wooded cleaves, bounded by streams and ancient trackways, as it was a thousand years ago, and although agriculture remains, the way of life for the farming community has changed beyond recognition.